Energy efficiency and conservation are a demand-side approach or often referred to as Demand Side Management (DSM) to meet the energy demand-supply balance. Contrast to supply-side management (SSM), DSM focuses on the efficient and effective way of energy consumption rather than ensuring efficient and adequate energy supply to the system. Energy efficiency and conservation are interrelated but have different meanings. According to the Energy Information Administration (EIA), energy efficiency is a measure to perform the same action using less energy (EIA, 2019). This may be enabled by using a technology which requires less energy. For example, using an LED light will draw less energy rather than an incandescent bulb. Meanwhile, energy conservation is a behavior or way which lead to less energy consumption. Turning the light when nobody’s at the room is a simple example of energy conservation. Both have similarity, the goal of reducing energy consumption.

Energy efficiency and conservation introduce various advantage to ensure the future availability of energy. In the consumer level, energy efficiency could lead to a lower bill. From an energy planning perspective, the implementation of energy efficiency and conservation allows deferring the cost of increasing the number of energy supply or building a larger capacity. Energy efficiency and conservation may lead to a least-cost solution while avoiding the long lead time of energy infrastructure construction. Less energy consumption will also result in lower carbon emission. One of energy conservation policy, energy diversification, promises a cleaner energy system with the utilization of renewable energy. The greater opportunity for energy efficiency and conservation policy is also supported with the global concern on the environment and climate change. Moreover, energy diversification could also prolong the breath of scarce energy supply. Utilizing less of fossil energy will preserve its limited reserve, which means energy security benefit.

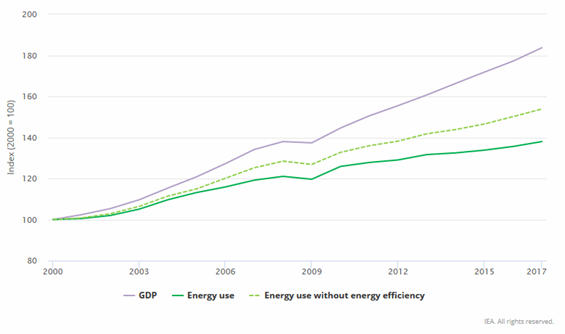

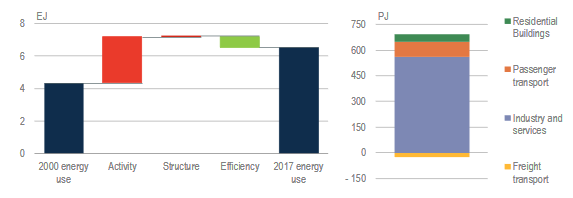

Figure 1 Global final energy use with and without energy efficiency (IEA, 2019)

From an economic perspective, a successful energy efficiency implementation will result in lower national energy intensity or other words; lower energy is required to increase the gross domestic product (GDP). The implementation of energy efficiency promises significant energy saving while maintaining the growth of GDP. Figure 1 shows that the global GDP increased even with the reduction of energy use from the energy efficiency measures during 2000-2017. International Energy Agency (IEA) reported that the energy efficiency policy could reduce 12% energy consumption compared to business-as-usual condition over the last decade (IEA, 2018).

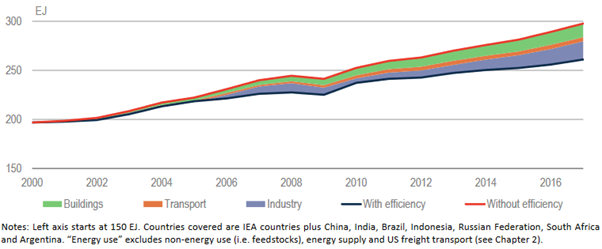

Energy efficiency and conservation could be implemented on wide sectors to achieve higher energy reduction impact. World Energy Council (WEC) suggest various technology implementation of energy efficiency and conservation in different sectors (World Energy Council, 2013). The implementation includes smart technology for oil and gas exploration and production (E&P) activity, cogeneration power plant for industry, to the smart grid to optimize the integration of renewable energy to the power system. IEA recorded that industry is the sector with most energy saving throughout 2000-2017 with 19 EJ or exajoule. The energy saving contribution of other sectors is illustrated in Figure 2. IEA also emphasize the contribution of shifting from energy-intensive manufacturing industry to the service industry to the global energy use reduction (IEA, 2019). Meanwhile, the increase of vehicle pushed the energy consumption to a higher level. These enclose that both economic and technical factor contributing to the energy saving level in different sectors.

Figure 2 Energy use in IEA countries and other major economies with and without energy savings from efficiency improvements by sector (IEA, 2018)

Despite the advantage of energy efficiency and conservation, the implementations are, however, challenging as it is related to people and industry’s awareness as well as supporting information. Another challenge is the financing mechanism of energy efficiency measures. The financial barriers include the availability of funds, the awareness of the financial actors, project development costs, risk perceptions, and limited institution capacity (APEC, 2017). Small energy efficiency incentive could discourage the energy consumer, especially industry, to implement energy efficiency measures. Lack of supportive government policy also gives an obstacle in achieving energy efficiency and conservation goal.

Indonesia shows its commitment in implementing energy efficiency and conservation by enacting the Government Regulation (PP) No. 70/2009 on Energy Conservation as mandated by the Law No. 30/2007 on Energy. The government regulation regulates the role of stakeholders, energy conservation program, standards and labeling program, energy management, and mandatory audit policy as well as incentive and disincentive. Government regulation No. 70/2009 also mandates the arrangement of the National Energy Conservation Master Plan (RIKEN). RIKEN should provide guidelines and roadmap for the implementation of the conservation program in Indonesia. The Energy Law requires the RIKEN should in line with the National Energy Policy (KEN) which is enacted by the GR No. 79/2014. KEN mandates the energy elasticity to be below 1 and the energy intensity reduction by 1% per year until 2025. The latest RIKEN was issued in 2005, before the enactment of both Energy Law and GR No. 70/2009. Until mid of 2019, the new draft of RIKEN is still under reviewed to align with the KEN. Considering the advantages of demand-side management, the government should rush the arrangement of the new RIKEN to establish the strategic guidelines for the energy efficiency and conservation program.

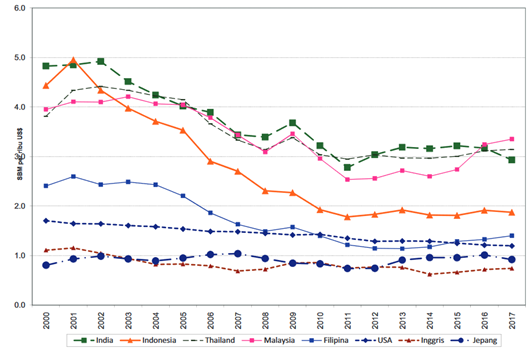

Figure 3 Energy intensity level of various countries (ESDM, 2018)

In Indonesia, the data from MEMR shows that the country’s energy intensity significantly reduced from 5 SBM/thousands USD to 2 SBM/thousands USD during 2001-2011, followed by a stagnancy until 2017. The level is, however, lower than neighboring countries such as Malaysia, Thailand, and the Philippines. The data shows that Indonesia could grow its economy by using lower energy. IEA addressed the economic activity shifting, from energy-intensive industry to less energy-intensive manufacture and service industry, and more efficient transportation modes contributed to the lower energy consumption (IEA, 2018). Contribution of industry scored the highest contribution to energy saving, followed by passenger transport. IEA also forecasted that the building and industry sectors have largest energy saving potential in the future. Space cooling and efficient appliances will play a significant role in an energy saving of the building sector. Meanwhile, less energy-intensive industry, such as food & beverage, tobacco, and textile, promises an improvement of energy intensity.

Figure 4 Decomposition of Indonesia final energy use and sectors’ contribution to efficiency gain (IEA, 2018)

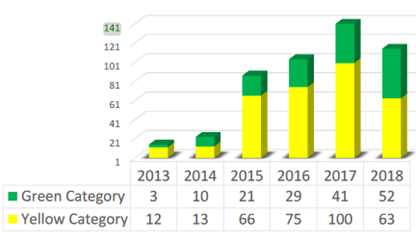

Indonesia’s government mandated energy users with energy consumption equal or more than 6,000 tons of oil equivalent (TOE) per year to perform energy management as mandated by the MEMR Regulation No. 14/2012 on Energy Management. The target for the regulation is the energy-intensive industry. Energy users require to assign an energy manager, plan an energy conservation program, perform an energy audit, implement the recommendation of an energy audit, and report the implementation of the energy conservation program. In 2018, the Directorate General of New & Renewable Energy and Energy Conservation (EBTKE) identified 278 companies and 346 sites consuming energy higher than 6,000 TOE. In 2015, Indonesia launched an online reporting platform, Pelaporan Online Manajemen Energi (POME). The number of the industry energy report was increased significantly since POME introduction. However, the number was still low compared to the total number of mandated industries. Another obstacle is the lack of certified energy auditor and manager in Indonesia. Energy audit results will play an important role in the arrangement of fiscal incentive, especially for corporate or industry. Hence, the government should pay more attention to the energy management and audit program. The incentive and disincentive policy should be more encouraging for the energy user to implement energy saving measures. More comprehensive energy consumption data will also beneficial for bottom-up energy planning.

Figure 5 Number of corporate reporting to EBTKE (Direktorat Jenderal EBTKE, 2019)

Energy standard and labeling policy were set by the ministerial regulation. Until 2019, the policy only covers compact fluorescent lamp (CFL) and air conditioning by the MEMR No. 18/2014 and No. 57/2017, respectively. The government plans to release a labeling system for other appliances, such as refrigerator, rice cooker, fan, and electrical motor. Therefore, only the building sector is affected by the policy. Currently, no labeling system for the transportation system, such as fuel efficiency label. The lack of policy coverage in the transportation sector may slow down the efficiency progress of the sector. With the large energy consumption of the transportation sector, fuel efficiency label will be a considerable solution for Indonesia in parallel with energy conservation measures, such as building a mass transport system and developing an alternative energy solution.

Energy efficiency and conservation incentives are stated in the GR No. 70/2009. The planned incentives are in the form of tax and duty facilities for energy saving appliances, a low-interest fund for energy conservation investment, and energy audit in partnership with government. Referring to the MEMR Regulation No. 14/2012, the MEMR provides an incentive in the form of an energy audit program with government fund using a partnership scheme. The regulation also states the forms of disincentive such as written warning, publication on mass media, fine, and energy supply reduction. The criteria of the eligible industry for the tax facilities should also be described in the Ministry of Finance (MoF) Regulation on Corporate Income Tax Reduction Facility. The latest MoF regulation, PMK No. 150/PMK.010/2018, has not included industry producing energy-saving appliances and energy service company (ESCO), yet. The duty facilities provision for energy saving appliances should revise related MoF regulation on Import Duty Facilities for Capital Goods. The ministry of finance is now considering the different fiscal option, such as value added tax (VAT) reduction, direct subsidy, rent promotion, soft loan, guarantee, and duty reduction for different sectors such as residential, commercial and industry, public, and transportation (Badan Kebijakan Fiskal, 2015). The government should comprehend the incentive provided to push the economic motivation of the industry player in implementing the energy-saving program.

The government also provides several programs and guidelines to increase people awareness about energy efficiency and conservation. Knowledge dissemination was conducted via public socialization collaborated with schools, educational institutions, and NGOs. The government also promotes energy efficiency by launching national energy efficiency award, Subroto Award, to recognize participant’s effort for energy-saving programs in 2012. The government should push more awareness of the industry decision makers as well as the financing institution to grab larger energy saving potential. Industry decision makers are the central actors in the energy management shifting. A knowledgeable leader on energy efficiency benefits tends to support energy efficiency initiative in the decision-making process. Increasing awareness of financial actor is also essential to eliminate the financial barrier of energy efficiency program (Institute for Industrial Productivity, 2012). Institutional coordination is required between MEMR and related government financial actors, such as MoF, Financial Service Authority (OJK), State-Owned Banks, PT. SMI.

In conclusion, Indonesia should also put the attention to the demand-side management, such as energy efficiency and conservation activities. The government should encourage the energy consumer to perform energy efficiency and conservation program. A strong and clear demand-side policy should be in action in parallel of supply-side policy. Government should make the pathway and policy clear, comprehensive, and directed. The enactment of new RIKEN should be the first step for clearer energy efficiency and conservation planning. Finally, interministerial coordination is required to address barrier from different sectors, be it technical or financial challenges.

References

APEC. (2017). Energy Efficiency Finance in Indonesia. Singapore: APEC Energy Working Group.

Asean Pacific Energy Research Centre. (2017). Compendium of Energy Efficiency of APEC Economies. APERC.

Badan Kebijakan Fiskal. (2015). Opsi Kebijakan Fiskal untuk Sektor Energi Dalam Mendukung Pembangunan Berkelanjutan di Indonesia. Jakarta: Badan Kebijakan Fiskal.

Direktorat Jenderal EBTKE. (2019, Januari 30). Skema Pelaporan online Manajemen Energi. Retrieved from WRI: https://wri-indonesia.org/sites/default/files/Presentation%20Pak%20Endra%20-%20ESDM.pdf

EIA. (2019, June 25). Efficiency and Conservation. Retrieved from EIA: https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/index.php?page=about_energy_efficiency

ESDM. (2018). Handbook of Energy & Economic Statistics of Indonesia 2018. Jakarta: ESDM.

IEA. (2018). Energy Efficiency 2018: Analysis and Outlooks to 2040. IEA.

IEA. (2019, June 25). Energy Efficiency 2018: Analysis and Outlooks to 2040. Retrieved from IEA: https://www.iea.org/efficiency2018/

Institute for Industrial Productivity. (2012). Delivery Mechanisms for Financing of Industrial Energy Efficiency. IIP.

Institute for Industrial Productivity. (2012). Energy Management Programmes for Industry. Washington DC: OECD/IEA.

Taylor, R. P., Govindrajalu, C., Levin, J., Meyer, A. S., & Ward, W. A. (2008). Financing Energy Efficiency: Lessons from Brazil, China, India, and Beyond. Washington DC: The World Bank.

World Energy Council. (2013). World Energy Perspective: Energy Efficiency Technologies. London: World Energy Council.

Wright, G. (2018). ISO 50001 Energy Management System.

Disclaimer: This opinion piece is the author(s) own and does not necessarily represent opinions of the Purnomo Yusgiantoro Center (PYC).