Subsidy is widely used by the government to protect the lower-income and vulnerable citizens from the high cost of energy source. However, it also has a negative effect on the budget balance and the appropriate use of energy. Therefore, a better approach in subsidy target is desperately needed in order to tighten the government spending and achieve an energy-efficient society. In Indonesia, the subsidy can be divided into two main groups, namely energy and non-energy subsidies. The focus in this writing will be the energy subsidies, which often took a major portion in the subsidy bills for recent years.

Besides the enormous number of populations, low energy prices from subsidies has played a crucial role in the energy consumption pattern in Indonesia. The main subjects for subsidy in the energy sector are for electricity, liquid fuel (gasoline, diesel, and kerosene), and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG). Table 1 shows Indonesia spending on energy subsidies, which divided into electricity and fuel and LPG. It indicates a major decline in 2015, 2016 and 2017 with a little jump in 2018.

Table 1. Energy subsidies spending in Indonesia (Merrill & Sanchez, 2019 and Indonesia-investments.com, 2018). ICP (Indonesian Crude Price).

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|

Subsidy Spending |

306.5 | 310 | 341.8 | 137.8 | 106.8 | 97.6 | 153.5 |

| Electricity (IDR Trillion) | 94.6 | 100 | 101.8 | 73.1 | 63.1 | 50.6 | 56.5 |

| Fuel and LPG (IDR Trillion) | 211.9 | 210 | 240 | 64.7 | 43.7 | 47 | 97 |

| ICP (USD/Barrel) | 112.7 | 105.8 | 96.5 | 49.2 | 40.2 | 50 | 67.5 |

In 2019 state budget, energy subsidies reach IDR 157.79 trillion from the total subsidy allowance of IDR 224.3 trillion. The energy subsidies consist of IDR 100.68 trillion for fuel and LPG and IDR 57.1 trillion for electricity (Rahardyan, 2019). Energy subsidy is very dependent on oil price and exchange rate to USD and might mess up the planned upcoming state budget if not addressed accordingly. In 2018, the energy subsidies increased significantly in the state revision budget. The initial allocation of IDR 94.5 trillion for energy subsidies increased to IDR 153.5 trillion in the revised budget. The main cause of this upsurge is the incorrect forecast of the oil price. The anticipated average oil price for 2018 was USD 48 per barrel, while the actual oil price was USD 67.5 per barrel (Alika, 2019).

Subsidy is indeed a burden for a state-budget balance and contra productive. Even though the primary purpose of subsidy is protecting the low-income and vulnerable citizens, subsidizing energy through price controls is not efficient. Every dollar spent on electricity subsidies will mostly flow to wealthier households due to their luxury lifestyle, which consumes more energy. However, removing subsidy entirely is not a wise decision either. Strategic measurement needs to be developed carefully first. When the subsidy is revoked, the price of electricity, fuel, and LPG will increase, and the household bills will rise as well. The increase in energy prices also has an indirect effect, for example, on consumer goods and services price. It is because consumer goods like food commodity also consume energy in the production process. Thus, higher energy costs are likely to raise goods and services price.

Moreover, The World Bank has analyzed the short-term effects of energy price increases on households relative to their income or consumption levels. The study shows that the indirect effects can be more than twice as large as the direct impact on the budgets of low-income households. It is particularly true since food and transportation make up a substantial part of their expenditure. In other words, the occurrence of subsidy has enormous benefits for lower-income households if proportionally compared to their expenses. Makes it more complicated to adjust the subsidy budget since there are around 40% of Indonesia populations relying on subsidy.

In order to overcome the subsidy burden while maintaining financial stability, the Indonesian government has executed several strategic steps to reduce the subsidies for electricity, fuel, and LPG. Indonesia is one of the top spending countries for electricity subsidies. The electricity price in Indonesia is set at a low level, and the government had to cover state-owned electricity producer (PLN) losses. In 2012, Indonesia government spent USD 10 billion for electricity subsidies. Consequently, the government developed a strategy to reform the electricity subsidies. In 2013, the electricity prices were increased to levels the costs, with the exclusion of small electricity connection namely 450 and 900 volt-ampere. Furthermore, following the decision in 2013, the Indonesian government decided to make a further reduction in electricity subsidies in 2017. The government withdrew electricity subsidies from households with 900 volt-ampere connections, excluding low-income household.

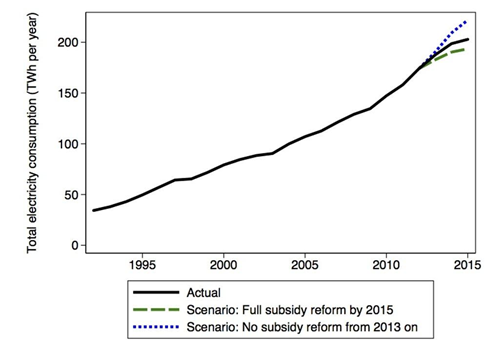

Burke & Kurniawati (2018) states Indonesia electricity subsidies reform had a positive impact on the efficient use of electricity. Figure 1 shows two scenarios regarding the electricity subsidies and compares them with the actual data. Figure 1 indicates that if there was no subsidies reform in 2013, the electricity consumption would continue to grow exponentially, while the full subsidies reform scenario would inhibit the consumption growth. According to the study, the cuts in electricity subsidies contribute to a 7% reduction of annual electricity use relative to the no-reform scenario. Furthermore, with full removal of electricity subsidies scenario, there will be an additional 6% of savings in electricity use.

Figure 1. Indonesia’s electricity use (Burke & Kurniawati, 2018).

The outcome of more efficient electricity consumption is not only in the form of a reduced subsidy bill but also lowering the pressure on the government to build new generation capacity. Some of Indonesia’s plans to build new coal power plants had been canceled altogether. Therefore, the potential increase of pollution from the planned new generators are eliminated, and the budget for building the related infrastructure can be allocated in other sectors.

On the other hand, a new subsidy reform for fuel has also been implemented since 2015. This achievement in reforming fuel subsidies has gained the world’s attention. Lourdes Sanchez from the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) reported that the Indonesian government saved USD 15 billion a year after reforming diesel and gasoline subsidies in 2015. The money then used to significantly increase Indonesia public investment to boost economic growth and reduce poverty.

In order to compensate the fuel subsidies reform, recently, in 2016, Indonesia’s “BBM Satu Harga” or One Price Policy was declared by President Joko Widodo. The program is supported by the Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources Regulation No. 36/2016 which was followed by Director General Oil and Gas Decree No. 09.K/10/DJM.O/2017. The program was officially launched on January 1, 2017, and has 148 districts in Indonesia as the target for project locations (Gass & Lontoh, 2017). The main purpose of one price policy is to bring justice regarding energy price for all Indonesian, since the fuel prices in remote and underdeveloped areas are still high.

Following the energy subsidies reform, Indonesia has also made progress in reallocating their subsidy budget to other strategic sectors. These sectors include health insurance, housing for low-income groups, clean water access, infrastructure, and other areas. However, the implementation of economic support for low-income households is still imperfect. The government still need to improve their methods in determining the targets, so the most needed one will get an access to the benefits.

The impact of energy subsidies reform in Indonesia has proved to be massive, but there are still some rooms for improvement. Thus, to progress further on continuously improving subsidy policy in Indonesia, we need to learn from the success story of other countries, for example, Canada, Argentina, and India. Canada and Argentina have successfully evolved their fossil fuel subsidies. They saved USD 260 million and USD 780 million respectively by removing some incentives to upstream fossil fuel companies in 2017 (Gerasimchuk et al., 2018). While in India, the effects of shifting the fossil fuel subsidies toward renewables have facilitated access to electricity and clean cooking fuels for tens of millions of the vulnerable.

These stories show that there are more methods in reforming energy subsidies, which will bring additional significant related benefits in the future. The savings from reforming subsidy policy can be redistributed to support the much-needed communities and incentivizing sustainable energy. The potential challenge will be an increase in oil price, which is the main drive for fuel cost. It is important to plan the compensation measures for the vulnerable, so that Indonesia stays on course with subsidy reforms despite the increase of oil price.

There are several plans that might be useful for the government to follow through to improve their subsidy policy. First, implementing regional electricity tariff pricing. The Indonesian government is advised to take the economic condition of each region into accounts. A number of economic indicators such as GDP per capita, purchasing power, and cost of production from each region are powerful to determine the appropriate local electricity price.

Second, better coordination with related ministries and organization for deciding the rightful target for subsidies. The strategic plan can also include the utilization of smart card technology, integrated with resident card and Indonesia’s banking system. Third, tax introduction for fossil fuels to account for ill health and climate damage. This plan supposed to support energy transition to renewable energy while increasing the state revenue. Fourth, Mujiyanto et al. (2015) recommends a quarterly fuel price adjustment for the most optimal way to accommodate inflation factor, oil price changes, and Pertamina profitability index.

All in all, delivering energy subsidies through price controls is a very inefficient way to protect low-income and vulnerable citizens. However, removing the subsidy without any mitigation plan can be fatal for the economy and social condition. Therefore, direct cash transfers or vouchers for low-income communities is the more appropriate and effective way to counter the negative welfare impacts of rising energy prices. It is also wise to evaluate other countries experience on how they reformed their energy subsidy policies and if possible, then implement it as well.

References

Alika, R. (2019, January 2). katadata.co.id. Retrieved from https://katadata.co.id/berita/2019/01/02/subsidi-energi-selama-2018-bengkak-jadi-rp-153-t-terbesar-untuk-solar

Burke, P., & Kurniawati, S. (2018). Electricity subsidy reform in Indonesia: Demand-side effects on electricity use. In Energy Policy (Vol. 116). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.02.018

Gass, P., & Lontoh, L. (2017). Indonesia energy subsidy news briefing. (January), 1–7. Retrieved from http://www.iisd.org/sites/default/files/publications/gsi-indonesia-news-briefing-january-2018-en.pdf

Gerasimchuk, I., Whitley, S., Beaton, C., Bridle, R., Doukas, A., Di, M. M., & Yanick Touchette, P. (2018). Stories from G20 Countries: Shifting public money out of fossil fuels. Retrieved from www.iisd.org/gsi

www. indonesia-investments.com. (2018, November 19). Retrieved from https://www.indonesia-investments.com/news/news-columns/indonesia-s-energy-subsidy-spending-far-above-target-in-2018/item9036

Merrill, L., & Sanchez, L. (2019, January 17). iisd.org. Retrieved from https://www.iisd.org/blog/success-stories-fossil-fuel-subsidy-reform

Mujiyanto, S., Supriadi, A., Darmawan, A., Prasetyo, B. E., Kurniasih, T. N., Oktaviani, K., … Alwendra, Y. (2015). Implementasi Kebijakan Ekonomi dan Energi Nasional 2015.

Rahardyan, A. (2019, Februari 14). Bisnis.com. Retrieved from https://ekonomi.bisnis.com/read/20190214/44/888792/jelang-debat-capres-17-februari-kebijakan-subsidi-energi-jadi-sorotan

Disclaimer: This opinion piece is the author(s) own and does not necessarily represent opinions of the Purnomo Yusgiantoro Center (PYC).