The utilization of biodiesel is part of Indonesia’s energy diversification to reduce the dependence on oil import and to provide alternative fuel for the transportation sector. Moreover, biodiesel’s enhancement can stimulate the economy by promoting more investment in the energy mix and leading energy security enhancement in Indonesia. However, the missing context in the biodiesel industry in energy security dimension and indicator may lead to energy insecurity.

Background

The Government of Indonesia (GoI) determines that the compulsory biodiesel program is an ideal scheme for enhancing national energy security. The mandatory program is still implemented due to the multiplier effects despite the pricing issue. For instance, it will save the foreign exchange, increase labour absorption, increase crude palm oil (CPO) price, decrease greenhouse gas (GHG) emission, and reduce fossil fuel. Biodiesel also has a positive potential as an export commodity. According to the Indonesian Biofuel Producers Association (APROBI), GoI will consider an initiation to boost the blending ratio into 50% Biodiesel (B50) in 2023 and even up to B100 after a successful car test in 2019. In contrast with the hindrance of mandatory blending of biodiesel B30 and B40. The GoI needs to integrate the road map with EV development, consider optimizing ISPO certification, intensifying the traceability and transparency in energy security indicators.

Behind the Scene of Biodiesel Mandatory Program

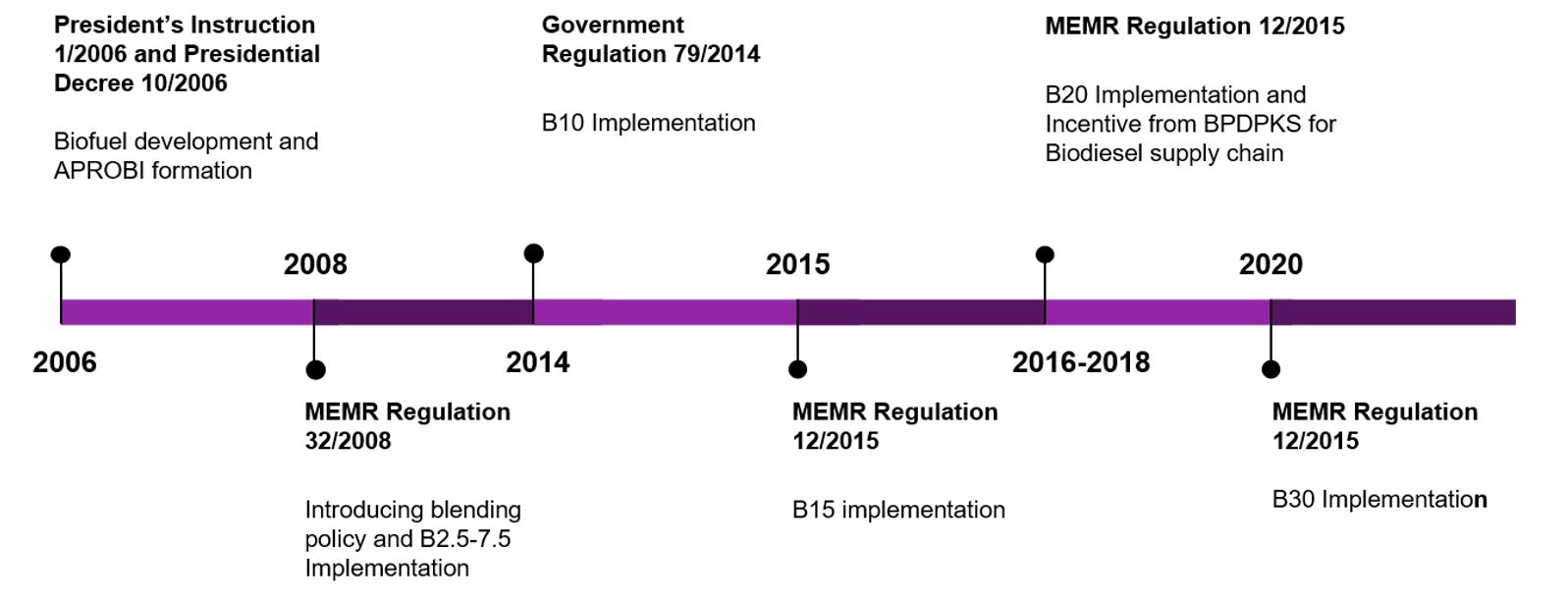

Figure 1 Indonesia Biodiesel Mandatory Program Timeline (Processed by PYC team)

Biomass energy has been developed in Indonesia since 2006 (figure 1) by introducing the President’s Instruction 1/2006 and Presidential Decree 10/2006. During the same year, the GoI also formed APROBI, responding to a strategy for fixing the balance of trade due to the rise of global oil prices. In 2008, Indonesia decided to opt out of OPEC. About that period, Indonesia started becoming a net importer due to the falling oil production and exploration compared to the increasing consumption.

The breakthrough was happening in 2008 when the Government of Indonesia (GoI) introduced the blending policy towards biodiesel through the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (MEMR) Regulation 32/2008. This blending policy proposes the 2.5-7.5% blending of Biodiesel with the composition 2.5-7.5% biodiesel fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) with 97.5-92.5% petrodiesel. GoI also announced Government regulation 79/2014 and utilized 10% blending of Biodiesel. Then, the policy smoothly revised into MEMR Regulation 12/2015 to equip changes in supply and demand. The same year, the government also set up the Indonesian Palm Oil Plantation Fund Management (Badan Pengelola Dana Perkebunan Kelapa Sawit, BPDPKS) as an instrumental institution for biodiesel stakeholders. In 2015 GoI increased the blending portion by 15% and continued to raise the amount by 20% (B20) in 2016.

Furthermore, MEMR Regulation 12/2015 implementation is in line with the president of Indonesia’s commitment at the Conference of Parties (COP) 21 Paris 2015 and Marrakech (Maroko) 2016 to reduce the emission to 29% by 2030. Biofuel is included with a 26% proportion as part of the 23% renewable energy (RE) mix in national energy consumption by 2025. The decree expanded the compulsory blending ratio of the Biodiesel Program to 30% or B30 in December 2019, and it has been widely implemented since January 2020.

Challenge Needs to be Tackled

This blending mandatory is employed to generate multiplier effects. However, there are several barriers that need to be overcome.

- There is strong criticism toward BPDPKS. On one hand, 90% of fund allocation goes to the biodiesel program to subsidize the price. On the other hand, smallholder palm plantations lack funds for rejuvenation to increase their productivity. Meanwhile, based on the Strategic Plan (Renstra 2020-2024), the GoI relies only on palm oil as a single source of biodiesel. With the significant increase in demand, this likely will cause scarcity in the future.

- Another challenge that needs to be tackled is the gap cost between fossil-based fuel and palm oil-based biodiesel. The price difference will cause an incentive load in the biodiesel industry.

- There is an issue about diesel engine efficiency (engine emission) with the utilisation of biodiesel. According to industrial player and researchers, Biodiesel will potentially cause technical issues in the diesel power generator.

- Based on President Regulation 44/2020 about the certification system of Indonesia sustainable palm oil (ISPO), the business player must be certified by ISPO to boost the Indonesia palm oil and biodiesel acceptability and competitiveness in the national market. However, by the end of 2020, the amount of certified smallholders’ plantation is only 20 certificates from 755 totals of certificates in spite of 35,4% of crude palm oil production (CPO) coming from smallholders farming. Furthermore, ISPO certificates are not accepted in some countries and lack traceability and transparency.

- The tremendous amount of palm oil demand will affect the environment catastrophe due to land-use change and lead to the biodiversity defect.

- The unintegrated policy between EV development and biodiesel will cause inefficiency and miscalculation of the programs in the future.

Recommendation

Although there are several obstacles, Indonesia still has hope in this program. Biodiesel has positive potential if the target market is not only domestic but also Export. During the pandemic, job sector plantations are also increasing. There are several recommendations that need to be considered to improve the biodiesel program.

Firstly, it is necessary to employ another feedstock in the future, considering the abundant amount of other feedstock, for instance, used cooking oil, second-generation feedstock and third-generation feedstock such as algae and microalgae.

Secondly, BPDPKS needs to consider the proper allocation of incentives in biodiesel programs to avoid social gaps, political issues, and fiscal hazards. The government should decrease the tax that is charged to smallholders plantation.

Thirdly, energy security is very attached to the specific context. Consequently, it is crucial to assess all the relevant and related aspects and indicators that can be used to quantify biodiesel’s energy security level. In this context, traceability is really important. Traceability is one of the toughest challenges for sustainability indicators in biodiesel. Requiring ISPO for all stakeholders will help the traceability of the palm oil supply chain in Indonesia with the provision of transparency in the data input and audit system both in big and smallholders.

Fourthly, to tackle the hindrance in the smallholder’s certification system, collective work such as cooperation can be the answer. The farmers who have small plantations are encouraged to join cooperation. Meanwhile, the cooperation could appoint a person in charge to monitor and evaluate the sustainability index as well as help in education and the system.

Lastly, There should be an initiation from the GoI to negotiate the acceptability of the ISPO certification system in the international market. This negotiation can be supported with the improvement of the traceability and transparency of our palm oil supply chain.

Disclaimer: This opinion piece is the author(s) own and does not necessarily represent opinions of the Purnomo Yusgiantoro Center (PYC).